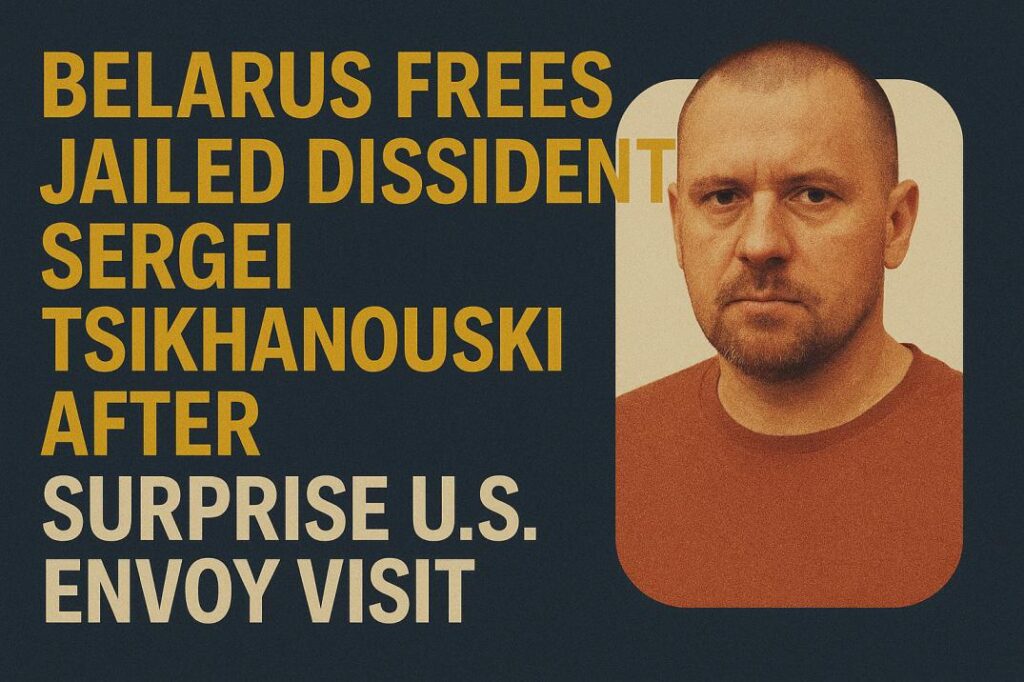

What Happened: In a dramatic turn of events in Eastern Europe, Belarus released one of its most prominent political prisoners, Sergei (Syarhei) Tsikhanouski, along with 13 other detainees, following a rare high-level dialogue with the United States. Tsikhanouski, a 44-year-old dissident and popular video blogger, had been serving a harsh 18-year prison sentence since 2021 for leading protests against Belarus’s authoritarian president, Alexander Lukashenko. His sudden release on June 21, 2025 – nearly four years into his term – came as a huge surprise and a glimmer of hope for Belarus’s beleaguered opposition movement. The development unfolded after an unprecedented visit to Minsk by a senior U.S. official: retired General Keith Kellogg, acting as an envoy for U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration on Ukraine and regional issues, met with Belarusian officials and reportedly with Lukashenko himself. It was the first visit by a top U.S. representative to Belarus in years (the U.S. and EU have largely shunned Lukashenko’s regime since his brutal crackdown on 2020 protests and his support for Russia’s war in Ukraine).

According to opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya – Sergei’s wife who ran against Lukashenko in the 2020 election and now lives in exile – the releases occurred shortly after the U.S. envoy’s meetings. Her team confirmed that 14 political prisoners were freed in total. A video posted on Tsikhanouskaya’s Telegram channel showed the emotional moment Sergei Tsikhanouski stepped out of a white prison van, appearing gaunt with a shaved head but grinning broadly as he embraced his wife amidst cheering supporters. Tsikhanouskaya, who has campaigned tirelessly for all political prisoners’ freedom, told reporters, “My husband is free. It’s difficult to describe the joy in my heart.” She quickly added that over 1,100 political prisoners remain jailed in Belarus and vowed to continue the fight for their release.

Background: Sergei Tsikhanouski was a key figure in Belarus’s pro-democracy movement. In early 2020, the charismatic YouTuber launched a campaign against Lukashenko’s long rule, popularizing the slogan “Stop the Cockroach!” (comparing Lukashenko to a cockroach, inspired by a children’s poem). He intended to run for president in the August 2020 election, but authorities arrested him in May 2020 on what were widely seen as fabricated charges. In his stead, his wife Sviatlana ran and became the main opposition candidate, galvanizing huge rallies. Lukashenko, in power since 1994, claimed a landslide victory in a vote critics say was rigged, igniting mass protests across Belarus. The regime responded with a brutal crackdown: tens of thousands were detained and many opposition leaders were jailed or forced to flee. In a closed trial in December 2021, Tsikhanouski was convicted of “organizing mass unrest” and “inciting social hatred” and sentenced to 18 years in a penal colony – one of the harshest sentences for any Belarusian dissident. Western governments condemned the verdict as political “revenge”. Alongside Tsikhanouski, several of his associates got 14-16 year sentences.

Since then, Tsikhanouski had been held in a high-security facility, reportedly under very tough conditions (there were reports he was placed in solitary confinement repeatedly). His wife Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya became the face of the Belarusian opposition abroad, recognized by the EU and U.S. as the legitimate representative of the Belarusian people. However, Lukashenko – buttressed by Russian support – weathered the protest movement and remained in power. Until now, he had shown almost no leniency toward political prisoners, with only a few minor figures pardoned in recent years.

Why Now – The U.S. Angle: The timing of Tsikhanouski’s release appears linked to geopolitical shifts. Belarus has been drawn deeply into Russia’s orbit, especially after it allowed Russian forces to use Belarusian territory to launch the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. However, with the war dragging on, Lukashenko finds himself in a precarious spot – facing Western sanctions and isolation, but also not entirely comfortable being Putin’s junior partner (there were even rumors of Putin pressuring Belarus to join the war directly, which Lukashenko has so far avoided). In this context, the visit by U.S. envoy Kellogg is extraordinary. It suggests backchannel diplomacy: possibly the U.S. offered some assurances or incentives (like limited sanctions relief or a promise not to push for regime change) in exchange for humanitarian gestures like releasing prisoners and maybe pledging not to directly enter the war.

Belarus’s state media did not explicitly mention Tsikhanouski in reporting Kellogg’s visit, only saying Lukashenko met an American official to discuss international security and Ukraine. But soon after, Belarus’s Foreign Ministry quietly informed some European diplomats of the prisoner release. Analysts speculate Lukashenko might be testing a slight thaw with the West or trying to portray himself as a peacemaker. It’s also notable that this happens while global attention is on the much larger Israel-Iran war (Story #1) – a quieter news cycle in Europe could allow Lukashenko to do this without appearing weak to his hardliners.

The U.S. State Department (and other Western governments) welcomed the news. Washington had always demanded “the release of all political prisoners in Belarus” since 2020; Tsikhanouski was one of the most high-profile. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken (who served under Biden and now continues under Trump’s term in this timeline) tweeted that the U.S. is pleased with these releases and will continue to press for democratic reforms in Belarus, but also supports Belarus’s sovereignty (implicitly reassuring Lukashenko the U.S. isn’t seeking to overthrow him by force).

Scenes of Joy and Caution: Videos of Tsikhanouski’s reunion with his wife and supporters were heartwarming. Sviatlana was seen wiping away tears of joy as she hugged Sergei, who until very recently she had feared she might not see alive for many years. For the opposition in exile, this is the first good news in a long time. Tsikhanouskaya’s camp stressed that it’s a first step: “We won’t stop until every last political prisoner is free,” she said. Human rights groups like Amnesty International and Viasna (a Belarusian rights organization, whose own leader Ales Bialiatski is jailed) also hailed the news while urging more releases.

Within Belarus, some remaining political prisoners reportedly reacted with cautious optimism. Families of other jailed activists are now hopeful that perhaps more pardons or releases could come. However, Lukashenko has a track record of using prisoners as bargaining chips, releasing some only to arrest others. So many observers are careful not to overread this as a sign of liberalization. “This is a tactical move by Lukashenko, not a change of heart,” said one Eastern Europe expert on BBC.

It’s worth noting that in 2015, Lukashenko similarly freed several political prisoners (including a previous presidential candidate) just ahead of engaging in talks with the West (that time he was seeking better relations due to Russia’s economic woes). History might be repeating in that Lukashenko is again hedging – possibly wary of being solely dependent on Russia amidst uncertain times (Putin’s war, and rumors about Putin’s own political future or health).

International Impact: The release of Tsikhanouski could slightly ease Belarus’s pariah status in Europe. The EU had cut nearly all ties with Lukashenko’s regime after 2020 and sanctioned dozens of officials. While one release won’t undo that, it could be a starting point for dialogue, especially if Lukashenko positions himself as a potential intermediary in the Ukraine war or in containing any spillover. Coincidentally or not, this comes as there have been speculations about a potential ceasefire or peace discussions for Ukraine, where Belarus could play a role (Belarus hosted prior peace talks in 2014 and 2015 for Eastern Ukraine).

For the United States, this is a diplomatic win that came at relatively low cost. The Trump administration can claim it successfully negotiated the freeing of political prisoners, which is good for its human rights credentials, even as it navigates complex geopolitics. It also shows that channels with even ostracized regimes can yield results through engagement – a point that might be underscored as a contrast to pure pressure.

What’s Next for Tsikhanouski: It’s expected that Sergei Tsikhanouski will leave Belarus soon to join his wife in exile (likely Lithuania). Many freed prisoners do so to avoid re-arrest. His 18-year sentence has been effectively commuted, but no one assumes he’d be safe or allowed to operate freely in Minsk. Tsikhanouskaya said he needs medical checkups and rest after the harsh prison conditions – political inmates in Belarus often face torture or neglect. Indeed, photos show he lost significant weight. But she also said he is “eager to continue fighting for a free Belarus” in whatever capacity possible. Having him by her side will bolster the morale and strength of the opposition abroad.

For Belarusians who desire democracy, this moment provides a ray of hope in an otherwise dark period. People shared on social media how Tsikhanouski’s defiant spirit had inspired them back in 2020, and how seeing him walk free rekindles their belief that change can come. Still, they know the struggle is far from over – over a thousand remain behind bars, including Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski.

Belarus state TV has largely ignored Tsikhanouski’s release or framed those freed as minor criminals pardoned by the president’s goodwill. The average Belarusian inside the country, living under censorship, might not even know the full story. But word of mouth and social networks (for those who access via VPNs) will ensure many know.

In summary, this is a notable diplomatic and humanitarian breakthrough. It highlights the shifting currents around Belarus and possibly opens a small window for easing repression. However, Lukashenko’s motives likely remain self-preserving rather than reformist. The coming weeks will show if this was an isolated concession or if more political detainees (like Bialiatski) might also be let out. Meanwhile, the Tsikhanouski family’s personal saga – separated by dictatorship, now reunited – stands as a powerful symbol of resilience against tyranny.